Author Matt Cuddy takes us on a ride through Part 1 in a two-part saga of the great Bert Greeves and his British two-stroke off-road empire.

Story by Matt Cuddy

Some say it was Bert Greeves mowing the lawn that gave him the idea to install the mower’s engine in his disabled cousin’s wheelchair, allowing the disabled man to travel greater distances with a gasoline-powered instead of a hand-powered wheelchair. Others say it was Bert’s huge ego that after he became a motor industry big shot, would allow him access to the paddock of racetracks, and gain the friendship of racers and owners alike, that decided the fate of Greeves. Whatever the case, Greeves became a legendary name in the British motorcycle industry, and it remains a marque of distinction among vintage off-road motorcycle enthusiasts to this day.

Oscar Bertram “Bert” Greeves was born in 1906, in Lyons, France, of English parents. His first job was an engineer with the Austin Motor Company at their factory in Longbridge, near Birningham, England, before setting up his own garage business in London. It was there that he built his first powered wheelchair for his disabled cousin Derry Preston-Cobb, using an engine from a lawnmower.

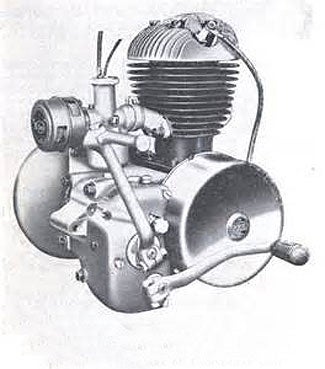

The first Greeves motorcycle appeared in 1954 and used a suspension system based off the design used on the Invacar. It incorporated a rubber torsion “spring” on both the front and rear suspension. Since Bert didn’t have an engine of his own, he decided to outsource a Villiers product, a two-cycle of 197cc displacement. Bert also designed what was to be later called “The Banana leading-link fork” a fork design that used the same torsion rubber elastomer found in the patented rear suspension system from the Invacar. Both front and rear suspension systems used an adjustable friction damping device to control compression and rebound damping. These bikes were built “one-off” and were in fact, prototypes.

This first prototype motorcycle also incorporated a Greeves design that used a large, light aluminum-alloy “Down Beam” cast front frame to hold the fork assembly and the front motor mounts of the Villiers motor. This piece was then cast into the round steel tubing that comprised the rest of the frame. Made from LM6 silicon-aluminum alloy, it was stronger than tubular steel and proved capable of standing up to the rough competition of international off-road trials. Aluminum skid plates rounded out the package, and protected the tender Villiers side and center cases from damage inflicted by bashing the assembly into large rocks, a common occurrence in trials riding. This first model was named “the Greeves” and came out in both trials and scrambler configurations. Both used the same leading-link fork and rear swingarm, with the big “rubber band” acting as a spring.

As chance has it, I owned one of these first “Greeves” motorcycles but didn’t realize what I had. It was being “thrown out” with the trash one Tuesday morning next to a riding buddy’s house, and we quickly pushed it into his back yard, to see what the heck it was. The seat was missing, along with the fenders, chain and most of the control cables. The gas tank was there, but badly smashed in on the clutch side. The only pieces left intact were the frame, engine/transmission assembly, wheels and front forks. What baffled us was the seeming lack of shock absorbers both on the front and back of the bike, obviously an English design. The Villiers motor was strange to say the least, with the fins on the barrel stopping halfway down, leaving the lower half of the barrel finless, showing the large transfer ports, intake and exhaust ports. A small Amal Monobloc handled the mixing chores, and it was badly damaged by what looked like blows from a hammer. But the oddest thing about the motor was how the flywheel attached to the crankshaft, and how you had to time the flywheel so the magneto would work. It was also missing an exhaust system.

Needless to say, once we got the damn thing running, it slipped time constantly. We finally fixed that problem by putting a long pipe over the wrench that tightened the reverse thread nut, and put enough torque on it to “cinch” the flywheel into the crankshaft’s tapered end, like a Husqvarna countershaft sprocket.

To make a long story short, the transmission was also shot, so we stuck the long-stroke Villiers motor in a Go Devil mini bike frame, running a direct drive off the engine sprocket, and somehow adapted an old Bing carb we had laying around. We also fashioned a “blooey” pipe that scared the crap out of anyone who rode the machine. It was timed at 52 miles an hour on El Mirage dry lake before exploding into several large, greasy parts. Good riddance. Like a disturbance in “the force,” I imagine old Bert must have had a few twitches that evening at home, while relaxing with his pipe and slippers “What on Earth just happened? Good Lord…”

The early success of Greeves with the prototype trials and Scrambler models carried Bert well enough financially to start producing a complete line of motorcycles that included street bikes. Real motorcycle production at the Greeves factory began in the autumn of 1953 with three models, one street bike, one trials machine and one scrambler. All featured the 197cc two- stroke, single-cylinder Villiers Mark 8E engine, with the infamous “Blooey Pipe” being used on the scrambler. The “Blooey Pipe” was a short header leading into a large, open, elongated, finned cast-aluminum funnel-shaped hole, just like two-stroke racing technology of the time dictated. It was loud and inefficient, but Greeves kept this design for three years and offered it as an option on later models. Bert was quoted as saying “We don’t get the power with a “chamber” like that of the open megaphone.” The ear-splitting racket these exhaust systems produced would cause modern-day two-stroke motorcyclists to cry, as the motor without any backpressure put the power right up around 4000 rpm, the Villiers’ maximum rpm limit.

Greeves, like about every other cottage motorcycle producer of the time, was forced by a lack of availability to use what was at hand, in this case Lucas brake and clutch levers. While being strong, Lucas Blades were uncomfortable, and made out of soft-chromed steel that would bend into unusable shapes instead of break off in a crash. The only good thing was the durability of Lucas controls, since a badly tweaked one could be taken to the campfire and bent back with some thick gloves, a wrench and hammer after a sufficient temperature was reached, i.e. right under red hot. I can remember one guy in our group who rode a BSA with the same Lucas blades, who cried out “I burnt my wittle hand!” when he tried without success to straighten out a deformed clutch lever while wearing his riding gloves and pounding on the lever with a 2-lb. ball peen hammer in the dirt. Neanderthals had nothing on Lucas levers, or Bert Greeves.

The adjustment collar was a big, four-pronged star, with a groove in the lever perch for the oversized English cable, which seemed to attract dirt and bugs and eventually would render the lever almost useless, like a hand exerciser turned all the way up. The clutch on these early machines would get hot, and start to slip, which required stopping and fumbling about with the star lever adjuster. Then, if the ride was long enough, you’d run out of adjustment entirely and be stuck with either 1) a bike you couldn’t shift or 2) a bike you couldn’t stop–perfect for trials competition! Of course, you could always stop, take the clutch case off and promptly lose the tiny part that held the cable in the clutch rod. A person usually did this only once in the life of the bike.

Of course, Italian hand controls were the sano way to go, but were not manly enough for the average Brit rider. “Blimey, I’m not gonna’ use them skimpy Eyetalian levers on me 500, I’d rather have one stuffed up me bum…criminey sakes.”

There was a bolt company based in India around that time, and the company produced knock-off hardened bolts for the English motor industry that, in all actuality, had the strength of peanut brittle. Since England at that time couldn’t decide if it wanted to be SAE standard, Whitworth or Metric, this substandard fastener manufacturing company took that as an opportunity to flood the market with cheap, brittle bolts that looked like the real thing, with the correct marking of a hardening level eight, and the appropriate little lines cast into the bolt head. Unfortunately you only knew you had one of these sub-standard bolts when it would snap off flush with the case, or head. That’s why the hands of many young British motorbike riders looked like those of an 80-year-old Skoda mechanic after using Easy-Out removal drills and removal bits a few dozen times. Bleeding into the afflicted snapped off fastener had no effect in helping dislodge the offending bolt. I know this from experience. But we’re getting off track…

Where were we? Oh yes, finding different Greeves models is sometimes a staggering feat, as with any British “cottage” motorcycle manufacturer of the time, because of the so many different types produced. Say old Burt and another member of his gun and riding club were sitting at the bar, having a Scotch after a few rounds of sporting clays, and his friend asked Burt: “Say, old fellow, I was wondering if I could get a motorbike built, not a trials, and not a scrambler, but a kind of “Trambler” that mixes the best parts of both. How much would that set me back old boy?” And in a few weeks, a one-off Greeves would be produced that no one knows about or has seen until that shed is opened up after 40 or so years, and there it is, a one-off Greeves, built for a friend.

Symptomatic of the new “cottage” motorcycle manufacturer in post-war England, Burt had a lot of friends, we’re sure, and as a result quite a few “special” Greeves models were produced that do not fit into any category of the production machines, so we’ll have to ignore those.

So what does one do, when there are close to 60 individual makes and models of Greeves motorcycles, and to go into detail on each one would take a book the size of the Guttenberg Bible?

We cover the milestone models, from the first period, to the middle, and then the end, when the Greeves factory closed its doors in 1977. So Sherman, please set the wayback machine to England, 1954, into the kitchen of one Bert Greeves.

Bert unveiled his first two motorcycles to the public in 1954. They were both dirt bikes, one being a trials machine, the other a scrambler model. These early bikes were both powered by a Villiers 197cc two-stroke engines. Greeves motorcycles were easily identified by two unique Greeves features: the leading link front fork and the cast aluminum “down beam”. This first model didn’t have a specific name, except for “Greeves” on both the trials, and the scrambler, and a model number of 20T. The engines that powered both machines were almost identical in porting, carburetor size and power output–all of about 12 thundering horses at around 4500 rpm. You could get a three- or four-speed gearboxs. The three-speed mostly fit to the trials bike, with the four-speed more commonly used on the scrambler.

You can see on the 1955 20T the magneto case covering the infamous “Bronze Flywheel.” Also, please note the “suspension” rods” in place of rear sprung shock absorbers, that were attached to the friction dampers under the seat. Both the swing arm and leading link forks were “sprung” by a big, round rubber band, excuse me, “Torsion Elastomer.” Funny, but remember when Suzuki and Kawasaki used rods to attach to the shocks? Déjà vu all over again.

One such bike, the 1958 Scottish, was a trials bike, with a 200cc Villiers engine, aluminum down beam, rubber “torsion” suspension on the forks, with conventional shocks on the back. With a wet weight of 198 lbs. Greeves sold every one it made, with new and experienced trials riders benefitting from the new theory of a lightweight, easy-handling trials machine that was a far cry from the old, heavy thumpers that proceeded them.

1958 Greeves Scottish Trial Bike. Note the absence of the rods and friction damper rear suspension, now replaced with conventional sprung shock absorbers. The forks still used the rubber torsion “elastomer” and friction damper.

Here it is, the list of known Greeves production motorcycles, by model, production years, name, and type of riding the machine was intended for, up to 1968. And there are a lot of them:

Model Production years Name Type

20TA 1958-59 Scottish Trials

20TAS 1958-59 Scottish Special Trials

20R 1954-57 Standard Roadster

20SA 1958-59 Hawkstone Scrambler

20SAS 1958-60 Hawkstone Special Scrambler

25SA 1958-59 Hawkstone Twin Scrambler

24SAS 1959-60 Hawkstone Special Scrambler

25D 1957-58 Fleetwing Roadster

32D 1957-58 Fleetmaster Roadster

25DB 1959-61 Sports Twin Roadster

24DB 1959-60 Sports Single Roadster

20TC 24TCS 1960 Scottish Trials

24SCS 1960 Hawkstone Scrambler

20SCS 1960-61 Hawkstone Scrambler

24TDS 1961-62 Scottish Trials

25DC 1961-64 Sports Twin Roadster

32DC 1961-64 Sports Twin Roadster

24DC 1961-63 Sports Single Roadster

20DC 1963 Sports Single Roadster

24MCS 1961 Moto-Cross Scrambler

24TE 1962 Scottish Trials

24TES 1962 Scottish Trials

24MDS 1962-65 Moto-Cross Scrambler

24MD 1962 Moto-Cross Scrambler

24INT 1961 International

25DCX 1962-63 Sportsman Roadster

32DCX 1962-63 Sportsman Roadster

24INT 1962 International

24TE 1963 Scottish Trials

24TES 1963 Scottish Trials

25DD Mk 1 1963 Essex Twin Roadster

32DD Mk 1 1963 Essex Twin Roadster

24RAS 1963 Silverstone Mk 1 Roadster

24ME 1963 Moto-Cross Starmaker Scrambler

24TES Mk 2 1964 Scottish Trials

25DD Mk 2 1964-65 Essex Twin (Dk Blue) Roadster

25DD Mk 2 1964-65 Essex Twin (Lt Blue) Roadster

24MX1 1964 Challenger Scrambler

24RBS 1964 Silverstone Mk 2 Roadster

24INT 1964 International

25DC Mk 2 1965 Sports Twin Roadster

24TFS 1965 Scottish Trials

20DC 1964-65 Sports Roadster

24RCS 1965 Silverstone Mk 3 Racer

24MX2 1965 Challenger Scrambler

24INT 1965 International

25DCE 1966 East Coaster Roadster

25TGS 1966 Anglian Trials

24MX3A 1966 Challenger Scrambler

24MX3C 1966 Challenger Scrambler

24MX3F 1966 Challenger Scrambler

24MX3G 1966 Challenger Scrambler

20DCE 1966 East Coaster Roadster

24RDS 1966 Silverstone Mk 4 Racer

24THSA 1967 Anglian Trials

24THSB 1967 Anglian Trials

24MX5A 1967 Challenger Scrambler

24MX5C 1967 Challenger Scrambler

36MX4A 1967-68 Challenger Scrambler

36MX4C 1967-68 Challenger Scrambler

24RES 1967-68 Silverstone Mk 5 Racer

24TJ 1968 Wessex Trials

24TJSB 1968 Anglian Trials

35RFS 1968 Oulton Racer

24DF 1968 City Patrol Police Roadster

24MX4 1968 Challenger Scrambler

For some reason, Bert’s list ends at 1968. We know that Greeves produced motorcycles, very competitive ones such as the Griffon, near the end of its life. We’ll cover those in Part 2 of this series.

But let’s start with the first Greeves dirt bike, produced in 1954. It featured a 200cc Villiers engine, the Greeves patented leading link “banana” forks and the cast aluminum beam that served as the front downtube on the frame. Bert produced a trials version and a scrambler, and both were an instant success.

We have to remember these first Greeves motorcycles were about 100 lbs. lighter than the classic thumpers from Matchless, BSA and Velocette, and as a result gave the 200cc Villiers long-stroke two-cycle a real advantage in performance. Stock, a stripped-for-dirt BSA Gold Star weighed around 300 lbs., full of fluids. Suspension technology, being in it’s infancy in 1954, a “Goldie” had about 4 inches of useable travel in the rear and about 6 inches in the front, with damping more suited for street use. Riding one at speed across rough ground could be called “thrilling” at best.

But remove 100 lbs. of ancient technology and hang some decent suspension off a new-style frame, with a two cycle engine, and you could see why Greeves became the dirtbike to have. Bert didn’t give this new bike a name, it was just a “Greeves.” And soon the off-road masses would be clamoring for Greeves motorcycles of all types and sizes. Bert must have felt elated at his success, and didn’t disappoint with the new motorcycles he produced in the few short years that followed.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices