Former AMA National Motocross and Supercross champion Ricky Johnson’s charismatic gift of gab can fill volumes in just a few minutes.

The colorful world of professional motocross is rife with champions who display as much personality as they do talent. In the 1970s, few could hold a candle to the character of the great Jimmy Weinert and the legendary Bob Hannah. In the 1990s, Jeremy McGrath wasn’t just the king of Supercross, he was also the captain of cool. And in the 1980s, Ricky Johnson had the charisma market cornered.

It’s a personality trait that continues to this day, a gift that allows the 51-year-old motocross legend to brighten the space around him whether he is telling a joke, receiving an award or doing something as serious as delivering a eulogy at a funeral. Johnson’s record of four AMA National Motcross titles (three 250cc and one 500cc), two AMA Supercross titles and four Motocross of Nations team-winning efforts speak to his talent, but his gift is his wit, his ability to always something interesting even when it means speaking the brutal truth as he sees it. He is the kind of person that can captivate a crowd for hours, and his thoughtful oration always seems to deliver a lot of emphasis in a short amount of time.

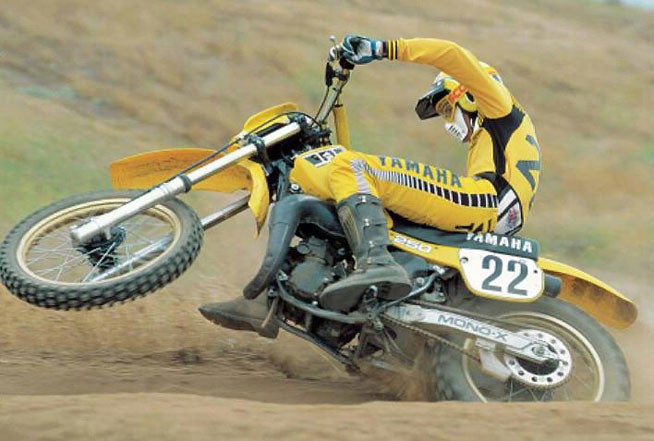

Sitting down with Johnson on the day that he received his induction onto the Yamaha Motor Corp., U.S.A. Wall of Champions left us with the same impression that it always has. He’s candid, forthright and funny. It’s also clear that he never forgets the people who have helped to get him where he is today. And although of all his AMA titles, only one came while he was dressed in Yamaha colors, he still considers the brand to be his spiritual home, making his induction all the more special.

This is obviously a very cool honor for you to receive.

It is a very cool honor, because it takes me back to being a little kid. My first motorcycle was a Yamaha GT60. I remember seeing that fat guy ride one in the opening scene of On Any Sunday. I was like, “A mini motorcycle? They make those?” My parents were able to buy me one when I was 6. Then I got a GT80 and started racing some TTs when I was 7. I quit for a while, then came back and started racing mini motocross on Yamaha YZ80 Bs, Cs. Ds and on up. Growing up in El Cajon, I had Broc Glover as a friend. He was four years older than me, but he was on the factory Yamaha team. You know, I still have his first press book. It has a picture of him and Rick Burgett and Bob Hannah, and he signed it to me. It says, “To Rick. I hope hope one day you too will be on this [team]. I carried that book to school with me every through sixth grade, seventh grade, junior high… The guys at Yamaha helped build me into who I am, from Mark Porter to Chuck Warren to Don Dudek to Ed Scheidler. They were like uncles to me.

You didn’t actually start with Yamaha by joining the race team, though.

No, I started with Yamaha by testing for them. My mom would drive me to meet with them after school, and I would just ride motorcycles all day long, and they would ask me questions, and I would work with the Japanese engineers. That really helped to shape and build me into the champion that I became. So, to come back here now and be next to guys like JD Beach and the road racers, and the motocrosses like Cooper Webb and Jeremy Martin, it’s a flash from the past but it’s also an honor to be mentioned with them.

Not to denigrate Honda, because obviously the majority of your championship titles came with them, but do you have the same kind of interaction and relationship with Honda?

No, and that’s the difference between Yamaha and Honda. Yamaha is very much about family. You know, when I left Yamaha and went to Honda it was a crazy time. Budgets were a big part of it, and Yamaha was cutting back and Honda was spending a lot more money at that time. When I left Yamaha, I cried—I literally cried, because they were my family. Larry Griffis, Kenny Clark, Cliff Lett—all those people I already mentioned—it was like getting a divorce and then having to go race against them. One thing that I have always respected, though, is that Bob Starr and Keith McCarty and all those guys never held it against me. They understood what I was trying to do, that I needed to make that change, and they always welcomed me back. When they called me for this, I was ecstatic. Honda doesn’t use me for anything. I’m not part of the family anymore. It was very much a business relationship—”we pay you well, you win races and when you’re done winning races, we hire the next guy”—and I get that. I get that. It’s like being an actor, working on a series, and when the series gets canceled they revoke your studio pass. But it still hurts your feelings. I thought I was different because I was special! [laughs]

Yamaha has continued to develop its heritage by continuing its mission to develop new riders and not necessarily just buy them. Certainly, other factories do that as well, but what do you think of Yamaha’s latest crop of young riders, such as Cooper Webb and the Martin brothers, Jeremy and Alex?

I love what I see. I love this generation of racers. There were some hard workers in my time, too, but then Jeremy McGrath came along and was so much better than everybody else in terms of his technique. He was so far above and beyond everyone, so connected with the bike.

Whether or not it was intentional, he kind of made it look like a rock star show, more partying, less training… Kind of like you.

It’s funny you should say that, because I will talk to some of the guys from Jeremy’s era, guys like Jeff Emig, and they’ll say, “Rick, that was partially your fault. They always portrayed you as this party guy who didn’t train all that much.” I mean, I had to train or else I would have been getting tired out there by lap six. It’s just that you had guys like Jeff Ward, Johnny O’Mara and David Bailey who were doing triathalons all the time, and I was just more focused on the riding. I was more flamboyant, and a lot of the younger guys thought they could just be more like me, but they might have taken a look at my stats to see when I got tired on the track… But that’s not taking anything away from McGrath. He came from BMX. He was purpose-built, and his technique was phenomenal. Nowadays, you see guys following the example set by Ricky Carmichael and how hard he trained. You hear more about the trainers, the Aldon Bakers and all of these guys. Looking at guys like Jeremy Martin and Cooper web, they’re like jockeys but they are so strong, and they race so hard. I love that. I will take balls and determination over style any day.

So what have you been doing to keep busy these days? You’ve obviously enjoyed a lot of success in four-wheeled off-road racing. Are you still doing that?

No. I’m not racing short course at this point, but at the same time I’m not going to say that I’m retired. I’m working very hard with the military. I switched RJMX to American Off-Road. My partner has 25 years in special ops, and he knows so many people in the special operations business, from British to Danish to American, Navy, Army, you name it. We just did a course with Seventh Group, which is the Green Berets, training them in motorcycle riding and off-road car driving techniques. I’m really proud of that because I feel like we are making a difference there. I’m also still doing some coaching, although I am not currently affiliated with any riders or teams.

And you still race the Baja 1000. In fact, you qualified number one for the 2015 race.

Yeah, but that is kind of spotty. Off-road racing and auto racing is all about bringing the money, and Red Bull is not going to fund me to start another team when they already have Bryce Menzies. But any time I can be there and do something, I show up and drive, because I still love it.

How about your own family?

Yes! I’ve been married 25 years, so I guess we’ve beaten the odds there. [laughs] My wife was 19 when we got married, and she had our first child when she was 21. We’ve had three beautiful kids, and I think that is our biggest accomplishment and our biggest joy. Luke, our oldest, is kind of following my path, although I didn’t want him racing motocross because I didn’t want him taking those chances. He races cars now, and he sponsored by Red Bull and Spyder Lights in the TORC series [Traxxas Off-Road Championship]. He was also my co-driver down in Baja this year. We qualified on the pole, which was great, and he was there to coach me and push me through it. Our middle son, Jake, is getting his Construction Management degree at Colorado State University up in Fort Collins, Colorado. Our daughter, Kassidy, is a senior the Art Institute in San Diego, and is doing interior design. So, watching them grow and watching them strive and push, and listening to their struggles and watching them work through it, is awesome. We are totally blessed. They’ve been healthy kids, and we are grateful for that.

What are your standout memories during your time at Yamaha?

There are two, and of course they are both race wins. The first one is winning the last AMA National ever held at Carlsbad Raceway [also the former home of the United States Grand Prix of Motocross]. I screwed up and got a bad start in the first moto, and then I worked my way up to fifth place. In the second moto I came out of the first turn fourth or fifth and ended up passing Johnny O’Mara and winning the moto. It was my rookie year, and I was on a full production Yamaha, and Scott Burnworth, Troy Blake and Eric Kehoe were on the works bikes. The other one is crossing the finish line when I won the 250cc National Championship in 1984. Ronnie Lechien and I had been going head to head that year, and it came down to the last moto. I was able to pull that moto off to win the title, and to have my mechanic Cliff Lett, who was instrumental in bringing me to Yamaha, standing on the side of the track with our pitboard, saying “’84 Champion!” with a big number one sign on it, was special. I almost dislocated both shoulders raising my arms. [laughs] That was cool.

If you could sum up your career in one word, one that you would hope everyone would remember it by, what would that word be?

More than anything, “determination.” There were days when I was the fastest guy on the track, and there were days when I got beat, but no matter which way it went I always fought to win. I fought to win for my team, my sponsors, my family and myself. If I could go down in the record books as a determined champion, that would make me happy.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices