If you think steering stabilizers (often called steering “dampers”) are just for the really fast guys who blaze across open desert terrain, think again.

While it’s true that the faster you go, the more you’ll appreciate the way these devices soak up impacts that could otherwise knock you off course, they also provide significant benefits at lower speeds. In fact, non-expert off-road riders aren’t always ready to compensate for jarring encounters with surface irregularities either, and they can be caught off guard when the front wheel touches down off center after being lofted. So, if a steering stabilizer can help us conserve energy, while making our technical errors and concentration lapses less costly, it’s probably worth considering.

Scotts Performance is a long-time leader in this market segment. Many racers use the company’s easily recognizable steering stabilizers, and a multitude of recreational riders will testify to the effectiveness of the product and the professionalism of its customer service. While we know that the Scotts stabilizers work well in the desert, we decided to see if one of their stabilizers would improve our experience out in the woods, and chose the sub-handlebar mounting option because it locates the stabilizer in a more protected position and makes the unit less threatening to the rider in a crash. For many bikes, Scotts offers two additional mounting options, one above the handlebar and one in front of the lower triple-clamp, with the damper jutting out above the front fender. Scotts also sells kits that include their own upper triple-clamp with built-in mounting points (at a higher price, of course).

The sub-mount includes a billet aluminum riser that fits in between the upper triple-clamp and the stock handlebar mounting posts. Our 2009 KTM 250 XC-W test mule came stock with four handlebar mounting possibilities. The asymmetrical posts could be rotated 180 degrees to fine-tune the fore/aft location of the bars, and they could each be mounted in either of two holes in the triple-clamp. Since the Scotts riser only reproduces the triple-clamp’s forward mounting holes, the rearward positions were sacrificed. The bars also wind up higher, since the riser is about an inch thick. Scotts sells handlebars with a shallower bend for those who wish to maintain stock height at the grips.

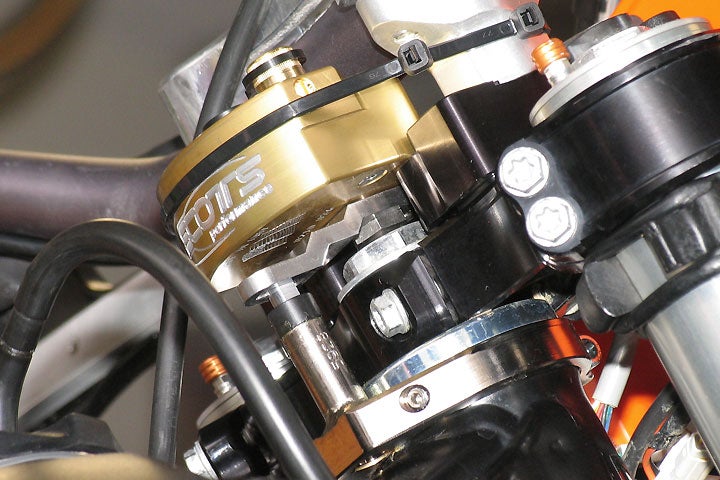

In addition to mounting the riser and eventually bolting the stabilizer to it, installation involved securing a stout “tower” to the frame (see photo). It’s this tower that links the stabilizer’s rotating arm to the bike’s relatively stationary chassis. We used a kit with a bolt-on tower, but Scotts also offers one with a weld-on alternative. Ours had a circular clamp that hugged the steering tube above the frame’s backbone. Mounting it required removing the upper triple-clamp and some very light filing of the local frame welds to achieve a snug, straight fit.

Installation was straightforward and simple, but there were quite a few steps for something that ends up attached to the bike by only several bolts; careful attention to detail was essential. Allow about 90 minutes for your first one; subsequent installations will go more quickly Note: You can easily move the damper unit from bike to bike, assuming all the mounting hardware (available separately) is already in place on each motorcycle.

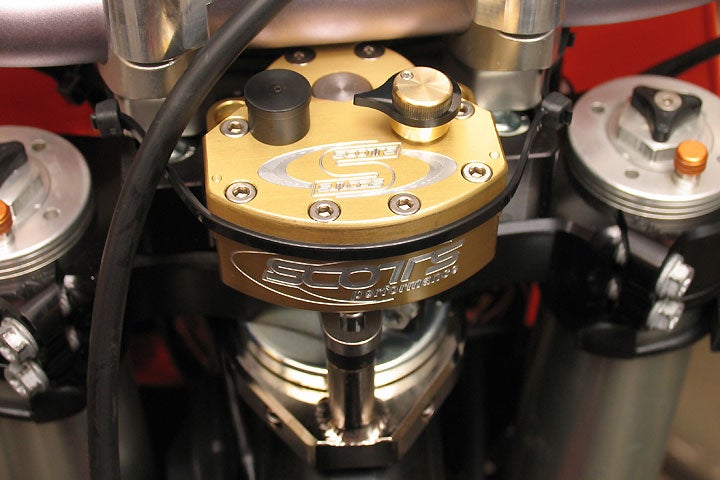

Once installed, the muted gold finish and precision craftsmanship of the Scotts unit added instant techno-bling to our KTM. One of the things these Scotts dampers are known for is their adjustability. A knob (right of center on this unit) allows the rider to increase or decrease the “base valve” damping resistance on the fly. The base valve is what restricts oil flow within the damper at relatively lower speeds (“speed” here refers to the speed of handlebar rotation, not ground speed). Next to this knob, a black cap covers the high-speed valve adjuster, which is simply a flat-head screw, much like those on adjustable suspension components. Two more adjustment screws can be found on the sides of the damper; each controls the “sweep” of damping influence on its respective side. Less sweep means the damping action fades out closer to the steering centerline; more sweep extends the range of damping influence outward toward the steering stops.

As the bars are turned, the damper’s rotating arm is held still at one end by the tower, while the other end turns a central shaft within the damper assembly. Similar to a linear damping mechanism, such as a fork leg, rear shock absorber or many cylindrical street-oriented steering stabilizers, oil is forced from one chamber into another through variably sized orifices, except this damper operates according to rotary, instead of linear, movement.

Adjusting the base valve changes the resistance routinely encountered at the bar; too much will make steering feel heavy. With proper adjustment, damping should be transparent, without any discernable change in resistance from before installation. Even though the bars aren’t any harder to turn, they end up feeling easier to keep straight. All sorts of micro-corrections you didn’t even know you were making drop out of the riding equation. This is a subtle change that’s only noticeable over time as you realize you’re expending less energy.

The high-speed circuit kicks in when there’s a sharp jolt to the steering, like when the front wheel receives a glancing blow from a root or rock (it’s impossible to simulate this with the bike at rest). Again, what you eventually notice is the absence of something: instead of careening off to one side or at least feeling a sudden jerk at the bars, the bike simply stays on course without any fuss. We’ve been content to leave the sweep set at the factory default, which is 22 degrees to each side of center.

At nearly $500 for damper and sub-mount bracket, this is a pricey accessory. Fit, finish and workmanship are all top-notch, and functionality is excellent, though not dramatic– in fact, it’s all about the removal of drama, which is a good thing. This probably isn’t the first modification you’ll want to make to your dual-sport or dirtbike, but once you’ve ridden with one, you won’t want to go without it.

Scotts Performance Products

2625 Honolulu Ave.

Montrose, CA 91020

818-248-2453

www.scottsonline.com

Steering Stabilizer (damping unit only): $330

Sub-Mount Steering Stabilizer Kit: (prices vary by application)

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices