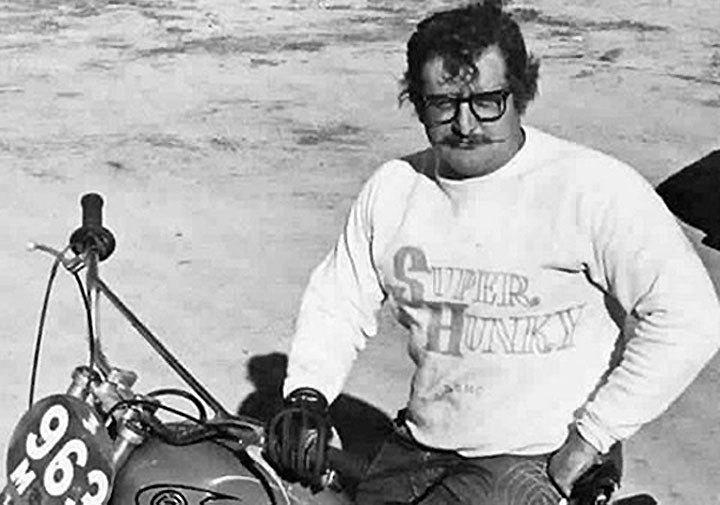

Note: During this period of time, Nate Sciacqua and I raced almost every weekend, and since I had no truck or trailer at the time, we had to use Nate’s hand-made nightmare of a trailer to get our DT-1 Yamahas to the track. So, oddly enough, this story is mostly true.–Rick Sieman

Fourteen Sundays in a row, Nate Sciacqua and I made the trip to Bay Mare Race Track, to (naturally) race motocross. This was several years ago, when we both rode Yamaha DT1s. DT1s that were painfully close to stock.

Naturally, we had to get the bikes to Bay Mare to race them. At the time, all I had in the way of bike transportation was a pair of homemade bumper racks–and no rear bumper on my scuzzy old station wagon. So Nate came to the rescue.

We used his trailer and split the gas money. Not a bad arrangement. Not bad at all. That was, until you looked at the trailer.

Ah yes, the trailer.

Nate made it himself. Believe me, you couldn’t find anything even remotely like it on the commercial market. It was approximately 16 feet long and wider than his car. The damn thing was heavy, very heavy, and had no suspension whatsoever. Nothing.

But it was strong. Giant beams formed the frame. And on top of these giant beams were slabs of metal that must have been on the side of a Navy destroyer at one time.

Nothing was left to chance in the construction of this jewel. Everything was welded firmly against everything else. I might add that Nate is not the best welder in the world, and he did all the welding by himself–much of it under very poor light. Several of the beads looked like a trampled Clark Bar.

On top of the metal plates, four huge pieces of channel iron were affixed. These turned out to be just wide enough not to accept a full-sized knobby tire. A large number of metal loops were put here and there to serve as bases for the tie-downs. And finally, on top of the flat part, a layer of ¾-inch plywood was bolted neatly and firmly. With enormous lag bolts.

We never really knew for sure, but it was estimated that the trailer weighed almost as much as Nate’s Chevy station wagon. It took quite some time to build a reasonable amount of speed. We clocked it once. It consumed exactly 4½ minutes to get to 55 miles per hour. And almost as long to get back down to zero again.

When completed, the trailer would easily carry four full sized dirt bikes in their assigned slots, and more if need be. At one time, if I remember correctly, as many as seven motorcycles were lashed down and transported.

But, for that one summer, the trailer was pressed into service to carry two gnarly Yamahas back and forth from Bay Mare.

And here’s where our true-life adventure began.

The road to Bay Mare–once you get away from the city–is a winding, twisting thing. Some of the curves are marked for 15 miles an hour, and the signs mean it. But, quite often, we were late getting underway, and this meant that driving had to be on the brisk side–if we were to get any practice in at all.

Translated freely, briskly meant that you couldn’t slow down too much for the turns, or the car would take forever to get back up to cruising speed again.

Nate always liked to slide a lot. Still does. So his towing technique was somewhat different from most people’s. It went something like this: The speed of the trailer combination would be, say, 45 miles an hour, and a corner with a 25 mph sign would loom up. First, Nate would make sure that no cars were coming in the opposite direction, then he’d swing a hair wide on the approach to the turn.

Reaching the proper point, he’d then smoothly stuff the front end of the wagon into the inside of the corner. Usually, at this moment in time, the trailer would protest mightily at the unwanted change of direction and slowly start to swing out in a nice, predictable slide. Naturally, the rear end of the wagon would try to follow the trailer. The secret was to keep the power on and steer in the opposite direction. Properly executed, the assemblage of car and trailer would get crossed up and stay crossed up through the entire corner. Engine rpm did not drop appreciably, and we would, as they say, keep on truckin’.

Normally, this type of cornering presented no problems. However, there were two problems which reared their ugly heads occasionally. The first was when the rear end of the trailer was allowed to hang out too far. Have you ever spun a doughnut? I mean a 7000-pound jointed doughnut? We did. Several times. Now, that was bad enough, but we would merely turn the vehicle around to its original direction and proceed onward.

The second, and biggest, problem was when a motorcycle would leave the trailer.

Nate had two sets of chains that were permanently hooked on the trailer. One good, strong item for his own personal bike, and the other for my bike. The second chain was not exactly the finest example of the chain-makers art, believe me. This thing looked like it had been welded in several places. It was not the most confidence-inspiring chain. But Nate insisted that chains were the only way to go–and what could I say? It was his trailer.

The first time we lost a bike, we merely laughed about it a great deal. There we were, sliding through a corner, just like always, when a loud PING! echoed off the orange grove alongside the road. I glanced back over my shoulder just in time to see a gold flash parting the leaves of an orange tree. At about 11 feet in the air. As soon as the wagon straightened out, we screeched to a halt and made tracks for the orange grove.

There, lying upside down under a medium-size orange tree, was my poor little 250 Yamaha. One bar was bent neatly back to the tank but, other than that, no serious damage was done. We struggled back up the embankment with the bike and loaded it back up on the trailer. A nut and bolt repaired the broken chain and, moments later, we were underway.

Next week, the second accident happened–on the same corner yet. Drive, drive, drive. Slide, slide, slide. PING! Another gold flash and the Yamaha blasted into the orange grove, slightly higher than the first time. Screech, stop. We scrambled down the slope to retrieve the bike.

Except we couldn’t find the damn thing. We must have hunted for 20 minutes and still couldn’t locate the whereabouts of that fine motorcycle. I think it would have been in that orange grove to this very day, if the gasoline from the tank hadn’t started leaking on my shoulder.

There it was! Stuck up in an orange tree. It took us nearly an hour to get it down. As we were pushing the undamaged bike up the slope, a stream of curses filled the air. Uh-oh. Time to get gone. The owner of the orange grove apparently wasn’t overjoyed about our visit.

We made a mental note not to lose the bike on that turn again.

And we didn’t. For several weeks after that. But one Sunday morning, late as usual, it happened again. PING! Followed by the now familiar flash of gold and the sound of breaking branches. We leaped over the fence–in a big hurry–and headed for the Yamaha. It was on the ground with a certain quantity of orange juice dripping from the slowly spinning front wheel. Flies were already starting to gather.

Fearing the approach of an irate farmer, we frantically pushed the bike up to the fence. Fence? That hadn’t been there the last time. Oh well. Fences were made to go around, or over.

We chose, regrettably, over. The very moment the frame tubes made contact with the fence, Nate and I were both hurled to the ground. What?

It took one more touch on a metal part of the bike to convince us that what we suspected was, indeed, true. An electrified fence. And there we were. With an electrified DT1 on our hands.

After several futile attempts to extract the Yamaha from the fence with our bare hands, we headed for the car and a piece of rope.

We arrived back at the bike about the same time as the orange grove owner did. He had a smile on his face.

“Doing a little riding, boys?” he asked politely.

Twenty minutes and twenty dollars later, we were back on the road heading for Bay Mare. The very next day, I bought a whole bunch of expensive nylon tie-downs. And I have used them to this very day.

Especially when I head out to Bay Mare with Nate.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices