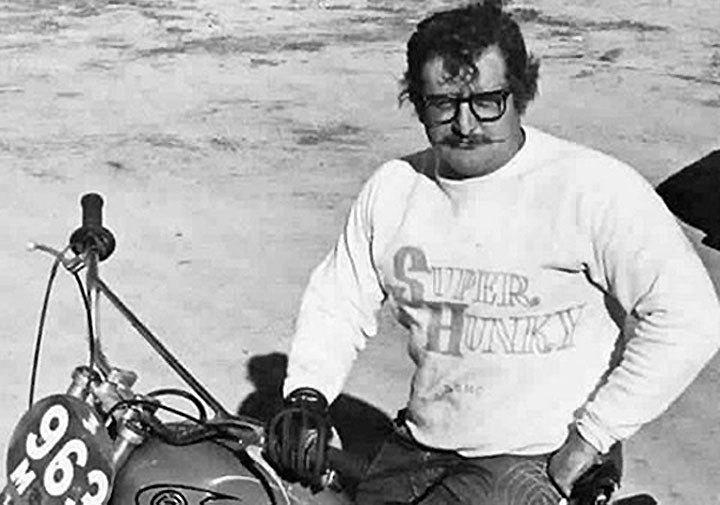

I don’t think I have the imagination to make this kind of weird crap up about ratbikes. I think maybe, just maybe, I’ve owned more bikes that cost me under a hundred bucks than anybody you’re likely to run into in your lifetime.

Several weeks ago, I actually won a trophy. A real honest-to-gawd trophy. It was just one of those super days that happen to every rider once in a while. My bike was a factory prototype 250 radial Maico, bristling with all manner of trick stuff. Horsepower oozed out of every crevice of the machine. It looked spiffy and was spiffy. You would have to be a blind toad to fall off of the thing.

At the time, this was the only machine of its type in the country. Friends of mine over at Maico said, “Take it for a ride, Rick, and see how you like it.” So, naturally, I entered the little jewel in a race. After the race, I was basking in the glory of a ride well ridden, when another rider came up to me and said (and I quote), “No wonder you did good. Take a look at that bike. If you had to ride a bike like I have to ride, you’d have finished next July, probably.”

I looked at his bike. It was a 250 Yamaha something or other; not too sure, because of all of the different things on it. Obviously the guy was riding on a budget. Things were held on with wire and duct tape, and the paint job looked like it had been done with a sock dipped in a bucket of 3M. Dents were all over everything, including the frame. It was not the best looking bike that I had ever seen.

But it set me to thinking. Thinking back to when I first started to ride dirt bikes, and just how many god-awful ratbikes I’ve owned.

Like a lot of guys, I rode streetbikes for a while before the dirt bug chewed a hole in my brain. All manner of streetbikes: skunky old Triumphs, multi-leaking BSAs, couple of Eye-talian 250 singles; you know–a little bit of whatever was available. Then, I went riding in the dirt, and it was time to get rid of the 750 Royal Enfield Interceptor and get me a machine with knobs and wide bars and number plates–things of that nature. Naturally, my first real dirtbike was a Bultaco Metisse that Jesus Christ couldn’t have kept running. Not on a bet. Part of the problem, more than likely, was because this particular ratbike had been so abused in the past. None of the previous owners had bothered to use an air cleaner, not even the Brillo pad that Bultaco offered as standard equipment.

Why break tradition? I ran the bike with no air cleaner, too. For maybe, ohhh, 10 or 12 miles, before it seized. Back to the shop. Rebuild. Out to the dirt. Ka-blam! Back to the shop. Out to the dirt. Erp-seize. Back to the shop.

Finally, someone suggested a filter. I was reluctant to part with the necessary $5.95, but the mechanic tactfully pointed out that I had already spent nearly $400 and it was worth a try. It was. With the air cleaner, the Bul would last almost an hour.

I lived with the Bul for almost a year, and in that period of time I pumped enough money in that machine to buy the entire state of North Carolina. Cash.

Friends would no longer ride with me. They knew it meant towing my bike back at the end of a rope. Every time. I was considering mounting an electric-powered nylon rope near the handlebars just to save time.

In desperation, I purchased a ratbike of a 250 BSA single to ride in the dirt–four-stroke reliability and all that. Well, it was reliable, but with an inch and a half travel in the forks and half that in the rear shocks, practical top speed was about 17 miles per hour. On a smooth trail.

Brainstorm. Put the BSA engine in the Bultaco Metisse frame. Reliability plus handling. It probably would have worked, too, if I hadn’t made those motor mounts out of thin aluminum. The first good jump and the engine fell out of the frame, and I ran over it.

There I was–a busted BSA and a busted Bultaco. Two of the biggest turkeys of all time. The State of California should have issued me a poultry license.

Financial pressures forced me to sell the Bultaco engine to another party for 30 bucks. I would not accept a check and would not care to meet that individual again.

A period of time passed and I saved my money for something that would do the job. Many missed meals later, I became the proud(?) owner of a stone stock Triumph TR6. In full street trim. Careful planning and much work later, I had the Trumpet down to a svelte 396 pounds. Dry. It was painfully stock, except for a well-worn Dunlop tire on the rear and a 4.00×19 trials tire up front. This fine unit was motocrossed, trailed, desert raced, entered in trials, and abused, until it finally died a year and a half later. No money was available to resurrect this classic, so the remnants were sold to the highest bidder. Proceeds went to the finance company.

Back to ground zero.

No bike, but still a Bultaco Metisse chassis. Much searching and scrounging yielded a Parilla 250 Scrambler for the princely sum of $35. Somehow, with the aid of an electric drill and a rat-tailed file, the motor got wedged in that feathery frame. It was a beautiful looking ratbike, and actually ran at one time. The length of the alley behind my house. A trail of ball bearings streaming out the ex¬haust pipe signaled its demise.

It sat for quite some time. Then, I found that most sought-after of all human beings—a fish. Traded him even-up for a 650 BSA (with a bent frame and collapsed front end) for the Parilla Metisse. It must have been the only one in existence.

An incredible stroke of luck en¬abled me to get the BSA running again. A garage sale (entire contents for $20) made me the proud owner of a bunch of rusty bike parts—one of them an intact Gold Star chassis.

Some research showed that the Goldie chassis and the 650 chassis were nearly identical.

Much hammering, grinding and drilling later, it was done: a true Beezer desert sled. And it ran. Not fast, and not very straight, but it ran. That was enough encourage¬ment to put some number plates on it and head for the great Mojave.

For all of this effort, the BSA rewarded me with nothing but one crash after another. Portions of my anatomy were quite literally strewn from one end of the Great Desert to the other. It just would not handle. Possibly the mixture of different parts from different years had some¬thing to do with it. I don’t know. All I do know is that it would get into a high-speed wobble at 35 miles per hour–or less.

The BSA was sold to another unsuspecting soul for a small sum of money, which was immediately spent for a 350 Jawa twin pipe (year unknown, but plenty old), set up for the dirt. This machine actually handled fairly well; it really did. But I think it could not have been putting out much more than 8 or 9 horsepower. Not to mention the fact that it weighed almost 300 pounds, needed seals, and fouled plugs. However, the machine did serve its intended purpose–it hauled me around in absolutely no style for a goodly long time. Never broke once. It must have had internals made of diamond.

Once, I fell off the bike and was knocked silly. In the back of my head I could hear the engine screaming its guts out at full throttle while lying on its side. Several minutes later, I got up to shut it off. The kill button was hit–it didn’t stop. I turned the gas tap off, but that didn’t help, ‘cause it always leaked anyway. In desperation, I yanked the plug wire with a handy stick. The engine kept howling away like there was no tomorrow. It was so hot that it didn’t need a plug to keep running. A regular Czech diesel.

Finally, I had to strangle the bike to shut it off. It more than likely would have run until it ran out of gas–which would have taken a week at the outside–big tank and very good mileage. The filter (an old nylon stocking) was ripped off and the mouth of the carb was sealed off by the imprecise “hand” method. Several times, I lifted my hand off the carb and the motor would start running again.

I waited quite a while for the motor to cease all mechanical noises before I raised my hand again. It finally stopped.

A faint red glow came from the engine and cases, so I thought it best to let the bike sit and cool a while. Ten minutes later, it started on the third kick and settled down to a spasmodic idle. The exhaust note sounded about normal–much like a bronchitic whale throwing up and belching in alternate strokes.

This machine proved to be not only indestructible in the engine department, but in the chassis, as well. Once I took a crash flat out in fourth gear (almost 45 miles per hour) and the front end hit a 20-foot Joshua tree. The tree was a mess and I was unhurt–the bike had nothing but a badly tweaked set of forks.

Normally, to straighten tweaked forks, you loosen all the front end hardware, give the right tug in the right spot, and the forks pop back in place. Well, the Jawa would do this all right, except while you were riding it, a random bump would tweak them right back out of line again.

Once, while jumping the Jawa alongside another bike, the forks flopped out of line and I executed the most fantastic cross-up ever done by any human being—without even trying. The landing, however, was something else.

I sold the bike to a buyer one dark night and watched as he tied it down in the back of his pickup. The forks stayed straight until he reached the end of the block. I believe it was the impact from running over a beer can that jarred them back out of line again.

This ill-gotten money enabled me to purchase another mount for the dirt. Believe it or not, a 200cc Gilera. There couldn’t have been more than a dozen of these things ever imported in the country, and they sure were ugly. They looked something like an anemic Ducati with a bad complexion. Ugliness notwithstanding, the bike ran fairly well, but parts were impossible to find, and many strange things found their way into and onto the Gilera. When the stock points burned up, those from a ‘49 Chevy were transplanted. When the generator died quietly, I used a giant dry cell battery for spark. When the gearshift lever broke off, I merely welded a ½-inch box wrench right on the shifting shaft. Craftsman, I believe. Held up fine after that.

Eventually, after much ridicule from my friends, I sold this fine machine to someone else. The very next day, it blew up in front of the local Taco Bell, maiming several parked cars with the flying metal. Apparently the new owner (an employee at said Taco Bell) was using the Gilera for transportation. No doubt, the Gilera rebelled and puked its innards in protest. Whatever.

A gold-tanked Yamaha made its way into my life, and showed me the joys of having a machine that was stone reliable and just moderately evil handling.

For quite some time, I was delighted, then fell to the lure of a good handling bike. A number of Greeves made their home in my danky garage and proved to be pretty decent bikes. I probably would have stayed with them, too, but the rest is history. Dirt Bike got started and I happened to be at the right place at the right time. Hot damn! Instant wallowing in bikes of all kinds, sizes and types. Riding, comparing and evaluating all the good iron. And eventually becoming the owner of the latest hot racing weapons. I was finally lucky enough to have good bikes underneath me.

But it’s only fair, don’t you think? I mean, after all, any man who owned and rode as many turkeys as I had in the past, deserved a break. I wasn’t getting any younger, you know.

So, if I happen to pass you on a race course sometime, and I’m on the new Gutwrencher G19MX, and you’re on a 200cc Gilera, please don’t feel bad. By the way, could I interest you in a Metisse chassis? Cheap?

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices